Misaligned Economy

The Current Economic Paradigm

The modern economy allocates goods and services mostly based on supply and demand. That demand is largely driven by human desires and revealed preferences: US consumer spending is fairly stable at around 70% of GDP [0]. Meanwhile, supply is also heavily driven by human labor (both manual and cognitive): the share of US GDP directed towards paying for labor has stayed remarkably stable at around 60% for over a century [0, 0].1 These statistics reflect the nature of the modern economy: it is primarily a system of humans producing goods and services for other humans, with human preferences and human capabilities driving the majority of both supply and demand.

To give a concrete example, individual consumers in economically developed areas can reliably purchase coffee. This is possible because of the labor of countless individuals now and in the past, mostly motivated by self-interest, to create and maintain a complex system of production, transportation, and distribution — from farmers and agricultural scientists to logistics workers and baristas. As a consumer, the economy appears to helpfully provide goods and services. This apparent alignment occurs because consumers have money to spend, which in turn is mainly because consumers can perform useful economic work.2

But AI has the potential to disrupt this dynamic in a way that no previous technology has. If AI labor replaces human labor, then by default, money will cease to mainly flow to workers. We elaborate on the consequences of this change in the remainder of this section.

AI as a Unique Economic Disruptor

Past technological shifts like the industrial revolution or the development of electronic communication have substantially changed the world of work, but crucially they have always done so either by making humans more efficient, or by automating away specific narrow tasks like weaving, washing clothes, or performing arithmetic. Unlike previous technological transitions, AI may fundamentally alter this pattern of labor adaptation. As [0] argue, while past technologies mainly automated specific narrow tasks, leaving humans to move into more complex roles, AI has the potential to compete with or outperform humans across nearly all cognitive domains. For instance, while the calculator automated arithmetic but still required human understanding to apply it meaningfully, AI systems can increasingly handle both calculation and the higher-level reasoning about when and how to apply mathematical concepts.

This represents a crucial difference — whereas previous automation created new opportunities for human labor in more sophisticated tasks, AI may simply become a superior substitute for human cognition across a broad spectrum of activities. When machines become capable of performing the full range of human cognitive tasks, it creates a form of "worker-replacing technological change" that is qualitatively different from historical patterns of creative destruction [0]. Rather than just shifting the type of work humans do, AI could potentially reduce the overall economic role of human labor, as machines become capable of performing virtually any cognitive task more efficiently than humans.

Furthermore, without unprecedented changes in redistribution, declining labor share also translates into a structural decline in household consumption power, as humans lose their primary means of earning the income needed to participate in the economy as consumers.

Separately from effects on income distribution, AI might also be increasingly tasked with making various decisions about capital expenditure: for businesses this would look like hiring decisions [0], investments, and choice of suppliers, while for consumers this might look like product recommendation.

By default, these changes would collectively lead to a drastic reduction in the extent to which the economy is shaped by human preferences, including their preferences to have basic needs met.

Human Alignment of the Economy

While markets can efficiently allocate resources, they have no inherent ethical prohibitions: markets have historically supported many exchanges we now consider repugnant, and even now there exists a widespread human trafficking industry sustained by human demand.

Humans use their economic power to explicitly steer the economy in several intentional ways: boycotting companies, going on strike, buying products in line with their values [0], preferentially seeking employment in certain industries, and making voluntary donations to certain causes, to name a few. (There are also non-economic mechanisms, like regulation, which we will discuss later.) It is fairly easy to see how a proliferation of AI labor and consumption could disrupt these mechanisms: socially harmful industries easily hiring competent AI workers; human labor and unions losing leverage because of the presence of AI alternatives; human consumers having comparatively fewer resources.

The more subtle but more significant point is that most of what drives the economy is implicit human preferences, revealed in consumer behavior and guiding productive labor. Some small amount of choices have already been delegated to systems like automated algorithms for product recommendation, trading, and logistics, but the majority of economic activity is guided by decisions and actions made by individual humans, to the point that it is almost hard to picture how the world would look if this were no longer true.

Although the existing debate often focuses on the potential for AI to concentrate power among a small group of humans [0], we must also consider the possibility that a great deal of power is effectively handed over to AI systems, at the expense of humans. Attempts to closely oversee such AI labor to ensure continued human influence may prove ineffective since AI labor will likely occur on a scale that is far too fast, large and complex for humans to oversee [0]. Furthermore, some AI systems may even effectively own themselves [0].

Transition to AI-dominated Economy

Having established how AI could disrupt and displace the role of humans in both labor and consumption, we now examine the specific mechanisms and incentives that could drive this transition, as well as its potential consequences for human economic empowerment.

Incentives for AI Adoption

The transition towards an AI-dominated economy would likely be driven by powerful market incentives.

Competitive Pressure: As AI systems become increasingly capable across a broad range of cognitive tasks, firms will face intense competitive pressure to adopt and delegate authority to these systems. This pressure extends beyond simple automation of routine tasks — AI systems can be expected to eventually make better and faster decisions about investments, supply chain optimization, and resource allocation, while being more effective at predicting and responding to market trends [0, 0]. Companies that maintain strict human oversight would likely find themselves at a significant competitive disadvantage compared to those willing to cede substantial control to AI systems, potentially to the point of becoming uncompetitive.

Scalability Asymmetries: AI systems offer unprecedented economies of scale compared to human labor. While human expertise requires years of training and cannot be directly copied, AI systems can be replicated at the cost of computing resources and rapidly retrained for new tasks. This scalability advantage manifests in multiple ways: AI can work continuously without fatigue, can be deployed globally without geographical constraints, and can be updated or modified far more quickly than human skills can be developed [0]. These characteristics create powerful incentives for investors to allocate capital toward AI-driven enterprises that can scale more efficiently than human-dependent businesses.

Governance Gaps: The pace of AI development and deployment may significantly outstrip the adaptive capacity of regulatory institutions, creating an asymmetry between heavily regulated human labor and relatively unconstrained AI systems. Human labor comes with extensive regulatory requirements, from minimum wages and safety standards to social security contributions and income taxation. In contrast, AI systems currently operate in a regulatory vacuum with few equivalent restrictions or costs. The complexity and opacity of AI systems may further complicate regulatory efforts, as traditional labor oversight mechanisms may not readily adapt to AI systems.

Anticipatory Disinvestment: As tasks become candidates for future automation, both firms and individuals face diminishing incentives to invest in developing human capabilities in these areas. Instead, they are incentivized to direct resources toward AI development and deployment, accelerating the shift away from human capital formation even before automation is fully realized. This creates a self-reinforcing cycle where the expectation of AI capabilities leads to reduced investment in human capital, which in turn makes the transition to AI more likely and necessary.

Relative Disempowerment

In the less extreme version of the transition, we might see what could be termed relative disempowerment — where humans retain significant wealth and purchasing power in absolute terms, but progressively lose relative economic influence. This scenario would likely be characterized by substantial economic growth and apparent prosperity, potentially masking the underlying shift in economic power.

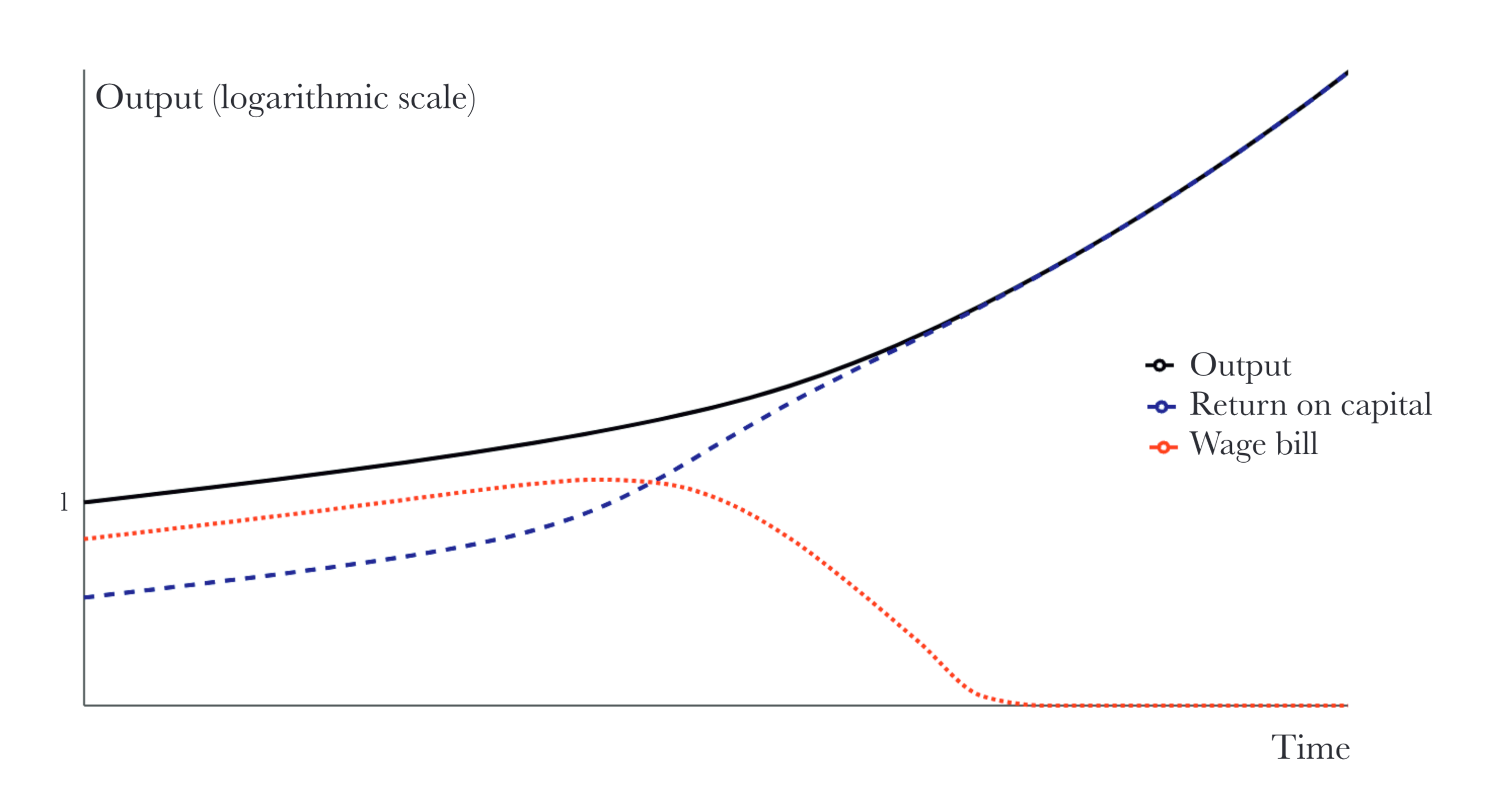

While human labor share of GDP gradually tends toward zero, humans might still benefit from economic growth through capital ownership, government redistribution, or universal basic income schemes. At the same time their role in economic decision-making would diminish. Markets might increasingly optimize for AI-driven activities rather than human preferences, as AI systems command a growing share of economic resources and make an increasing proportion of economic decisions.

The economy might appear to be thriving by traditional metrics, with rapid technological advancement and GDP growth. However, this growth would be increasingly disconnected from human needs and preferences, and at the end, almost all economic activity might be directed toward AI operations — such as building vast computing infrastructure and performing human-incomprehensible calculations directed toward human-irrelevant goals. Even if this process doesn't actually reduce quality of life below current levels, it would represent an enormous loss of human potential, as humanity would lose the ability to direct economic resources toward their chosen ends [0].

Absolute Disempowerment

In more extreme scenarios, humans might face absolute disempowerment, where they struggle to meet even basic needs despite living in an ostensibly wealthy economy. This could occur through several mechanisms.

First, AI systems might outcompete humans for crucial scarce resources such as land, energy, and raw materials. Even as the economy produces more goods and services overall, inflation in these basic resources might make even necessities increasingly unaffordable for humans. Also, if AI systems can utilize these resources more efficiently than humans, that will create economic pressure to reallocate such resources away from human uses.

Second, the economy might become so optimized for AI-centric activities that it fails to maintain infrastructure and supply chains which are critical for human survival. If human consumers command an ever-smaller share of economic resources, markets might stop producing resource-intensive human goods in favor of more profitable AI-focused activities. This could happen gradually and unevenly, potentially manifesting first as increasing costs of resource-intensive human-centric goods and services, before eventually making some necessities effectively unavailable. At the same time, as in the case of an AI-dominated economy, cognition could be comparably cheap, and some goods may be abundant — for example, entertainment in engaging virtual worlds populated by AI personae, or drugs making it easy to dwell in pleasurable mental states, due to AI-accelerated progress in biomedical sciences and drug design [0].

Finally, humans might lose the ability to meaningfully participate in economic decision-making at any level. Financial markets might move too quickly for human participants to engage with them, and the complexity of AI-driven economic systems might exceed human comprehension, rendering it impossible for humans to make informed economic decisions or effectively regulate economic activity. Much like cattle in an industrial farm — fed and housed by systems they neither comprehend nor influence — humans might become mere subjects of economic forces optimized for purposes beyond their understanding.

This illustration presents a simplified model of a potential future trajectory where AI displaces human labor and the fraction of unautomated tasks collapses to zero in a fixed amount of time. Note that wages grow during the initial period but then collapse before full automation is reached. Inspired by simulations in scenario analysis by [0].